A Female Artist of the “Lost Generation”:

Turning Anxiety and Darkness into Light and Hope

“I believe in the good and spiritual, the free, the true, the bold, the beautiful and the right, in a word in the sovereign serenity of art, this great antidote against hatred and stupidity.” Thomas Mann

Exhibition in the Nebbinian Gardenhouse, Frankfurt am Main, 1958

It’s a matter of choice: to see the darkness or to create light.

Alice Pairan chose to depict light in one of the darkest eras of human history. In this choice lies her legacy as an artist, a woman and a mother who strove to highlight the beauty largely forgotten in the dark days surrounding her world.

The life story of Alice Pairan’s bears witness to the significance of her motto. Born in 1911 in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, her childhood years were marked by not only the catastrophic effects of the First World War, but also the challenges that her family faced.

Her father, Wilhelm, was a highly talented and passionate orchestra violinist, whose ambitions were cut short, as he was obliged to abandon a musical career after his father passed away to take charge of the family excursion destination and restaurant “Wilhelmshöhe”. This imposed separation from artistic creativity left its mark on him in the form of an ever-present melancholy. Alice’s mother Katharina, once courted by organ entrepreneur Farny R. Wurlitzer, held a leading position at the German branch of the Triumph Cycle Company and provided a balanced pragmatism and professional female role model.

Alice Pairan’s parents, 1910

Alice age 4, 1915

Their innate artistic leanings were an important influence behind Alice’s talent, desire and ultimate recognition in her pursuit of the arts.

Despite being a young child, Alice felt on her family and surroundings the effects of the First World War, ending in a humiliating defeat for Germany capped by the treaty of Versailles.

Despite the ailing economy, Alice grew up during those hard years into an intelligent, radiant and beautiful young woman, overlooking the negative and focus on the bright and the positive. This tendency would later become evident in her artistic expression. After completing schooling, Alice, an only child, wanted to study acting – a choice her parents discouraged. As a compromise, she decided on fine arts and was accepted into the highly competitive Frankfurt Städelschule in 1931 to study painting and batik/textile printing.

Alice with two fellow students at Städelschule, 1931

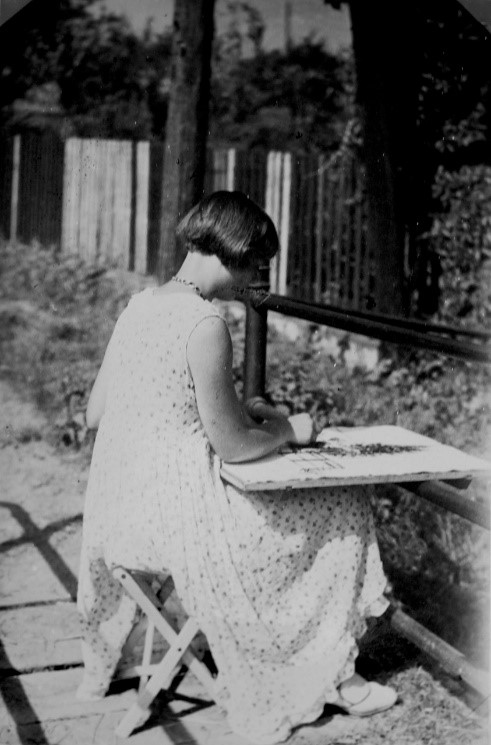

Alice drawing in Amorbach 1932

As a student, Alice soaked in the inspiration around her, exploring many disciplines. Her professors recognized her extraordinary talent and selected her to study under the patronage of acclaimed painter Dr. Willi Baumeister, who belonged to the same circle as Paul Klee and le Corbusier. However, Baumeister’s career at the Städelschule and his mentoring role for Alice were cut short by the Nazis and he had to leave his post in 1933.

In spite of this setback, Alice persevered and continued her education under another important figure: Professor Franz Karl Delavilla, with whom she further broadened her artistic skills by adding tempera, aquarelle, lithography and mixed media to her range.

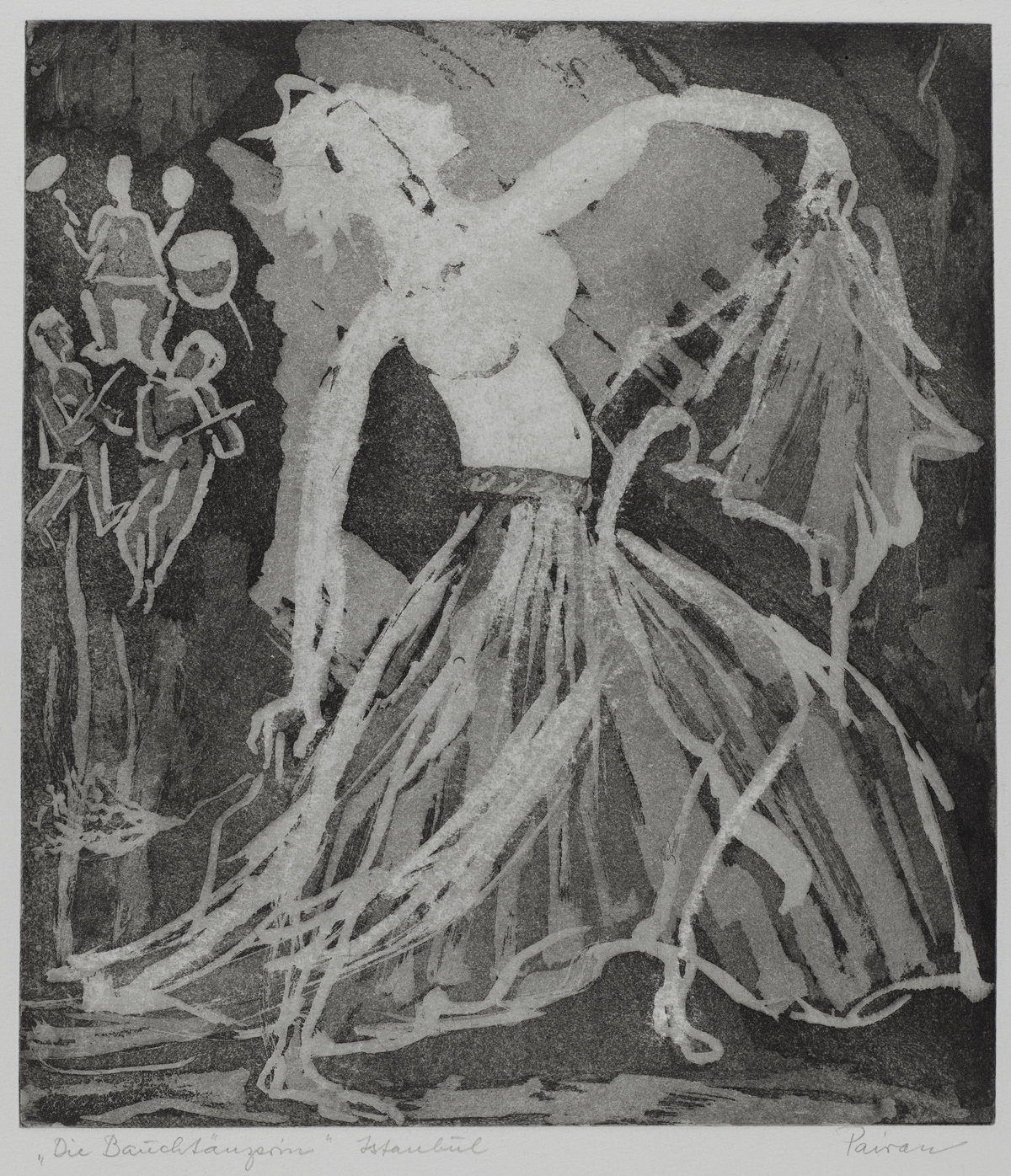

Alice 1932 expressive dance

Die Bauchtänzerin / The Belly Dancer

35×28 cm, Etching Aquatinta, ca. 1970

After graduating in 1935, Alice moved back to her parental home and established her own studio. With her studies completed, she got engaged to Kurt Hauser, owner of a printing and office supply company, with whom she had formed a strong romantic bond. They married two years later in 1937.

Engagement with Kurt Hauser, 1935

Alice with baby Ursula, 29x41cm, 1942

Those were unsettling times as Germany witnessed the meteoric rise of Adolf Hitler, who quickly thrust the country into the Second World War. Alice’s opportunities further diminished during the wartime period due to her parents’ enlightened decision not to join the Nazi party and refusing to display a “Jews not welcome” sign above the “Wilhelmshöhe”. This created constant suspicion and harassment from the authorities. Alice, nevertheless, continued to be a prolific painter and produced a considerable body of work during those dark times.

Two years into the Second World War, she gave birth to her only child, Ursula, in 1941. The insecurities of a war-torn country forced Alice and her little daughter to move in with her aunt in rural Allendorf, far removed from the city life she knew. There she discovered new vistas and subjects for her creations. It was in this unlikely setting that she established herself as a bona fide artist and used her painting to barter for daily supplies such as food and clothing.

While in Allendorf, sadly, her studio in Frankfurt, together with all her paintings, were bombed and burnt to the ground. The loss of the entire body of her work produced up to 1943 was perhaps her greatest personal injury caused by the war. Moreover, her marriage to Kurt did not survive the long physical separation and the strains of the war, exacerbated by his failing health.

Now a single mother, but with a stronger art experience and tested resilience, Alice returned to Frankfurt at the end of the war, only to discover that the family’s property “Wilhelmshöhe” had been confiscated by US troops. Within another year, she lost both her parents.

Despite these tribulations, Alice persevered and her creativity soared. Tirelessly innovative, her entre into the international art scene came in 1948 with unveiling 15 pieces at an exhibition in Darmstadt. From there, her career took off in earnest. Many of her inspirations stemmed from frequent travel and explorations, always her sketchbook at hand, capturing new subjects and atmospheres. In her hometown, the opera house was one of her favourite subjects and she contributed to its “Wiederaufbau” through dedicated exhibitions, which won her several awards.

Opera House, 60 x 46 cm, Collage with black ink on glass

Over the next 30 years, Alice Pairan was sought after by galleries from Germany to the Middle East. Other than the most notable German cities, she exhibited in Paris, Lyon, Prague, Athens, Rome and Beirut. In addition, she received many prizes, including several at the Ancona Biennale and Annuale. She continued creating, exhibiting and collaborating with avant-garde artists such as Walter Hanusch into the 1970s, while keeping contact with fellow painter Fritz Winter and teaching young talents. Alice became one of the pillars of the Frankfurt art community, hosting salons for art lovers, promoting women artists in particular and tirelessly supporting women empowerment through Zonta. She passed away in 1979 at the early age of 68. A commemorative calendar of her work was published the following year.

Exhibition in the Nebbinian Gardenhouse, Frankfurt am Main, 1958

Alice Pairan in her home in Frankfurt, 1966

Alice in Norderney, 1957

Alice (second from left) at ZONTA event in Basel, 1972